- Home

- Alice Hoffman

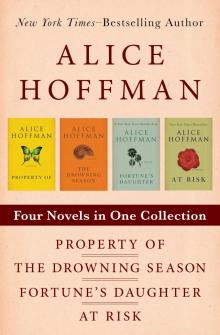

Property of / the Drowning Season / Fortune's Daughter / at Risk

Property of / the Drowning Season / Fortune's Daughter / at Risk Read online

EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

LOVE TO READ?

LOVE GREAT SALES?

GET FANTASTIC DEALS ON BESTSELLING EBOOKS DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY!

Property Of, The Drowning Season, Fortune’s Daughter, and At Risk

Four Novels in One Collection

Alice Hoffman

Property Of

A Novel

Alice Hoffman

With thanks to Maclin Bocock and Albert J.

Guerard, and to Patricia Crowe, for many kindnesses

during the writing of this book

JANUARY

ONE

NIGHT OF THE WOLF

1

“Look,” I said, “I’m going with you.”

Snow was falling and the moon was howling light onto the Avenue. It was a night for skidding tires and Orphans on the street. I waited for his answer.

“Get lost,” said Danny the Sweet.

“Danny,” I said, “what kind of an answer is that? That’s an answer I won’t accept.”

“Eh,” said Danny, “you got no choice but to accept it.”

I considered words of persuasion. “Hey,” I said, as we stood in the doorway of Monty’s candy store with the darkness of a January night surrounding us. “I can take care of myself.”

“What do you know?” said Danny the Sweet. “Girl, you know from nothing.”

But did I care? This was no time for loose talk from this eater of Milky Ways, from this driver of a fifty-seven Pontiac. No.

“I know enough.” I smiled.

The Sweet leaned against the stone of Monty’s doorway and sipped ginger ale. Inside Monty was closing up for the night, chasing away the neighborhood corner kids, muttering over a gin and tonic, and wiping the linoleum counter clean with an ancient dishcloth.

“That sounds like a threat,” said Danny the Sweet.

I was silent, and I smiled at my old friend the Sweet.

“If you are threatening me, I got only this to say,” said the Sweet, “don’t try it.”

But I knew Danny the Sweet, and I had no fear. I lit a cigarette and exhaled the smoke into the winter air.

“Girl, what you think you got on me?” Danny gulped ginger ale. “You can’t prove nothing.”

“What I got on you,” I said, “would make your mama cry.” I exhaled slowly.

“You talk too much for me to take you anywhere,” said Danny.

A weak argument. Hadn’t I watched him change the oil of his Pontiac enough times? Hadn’t I coughed my way through drugstores, hacking madly and buying up shelves of Romilar and dozens of candy bars for the Sweet?

I was silent.

“You know you do,” said the Sweet.

“Hey, I’m no fool,” I told him.

Danny the Sweet turned his back on me. “You see this?” he said. I could see clearly in the reflection of neon the words written in red and gold on the back of his jacket.

THE ORPHANS

Danny turned around to face me once more. “They don’t take no trash,” he confided.

“I’ll behave.” I smiled; any lie to meet the Orphans.

“Especially not tonight,” continued Danny.

Tonight was a night remembered in the doorways of candy stores all along the Avenue. The Night of the Wolf. The hour when the Orphans went hunting their enemy from the south end of the Avenue—the Pack; a night to celebrate when the snow is covering alleyways and the moon shines white.

“I swear it, Danny,” I said. “I won’t cause trouble for you.”

“Maybe if you showed some respect for me,” said Danny the Sweet.

Ah, he wanted me to pay for an introduction to the Orphans. What the hell, I’d fake it.

“I respect you,” I said.

“Eh, you never have.” Danny unwrapped an Almond Joy. “Since we were kids, you never have.”

Well, that was true. But I liked him anyway; even if the mixture of codeine and chocolate had rotted his brain.

“You all think you’re smarter than me,” said Danny.

“Ah, Danny, I never said you weren’t smart. I never said I didn’t respect you.”

Ice was forming on my boot, Monty had already dimmed the neon of the store, and the Night of the Wolf would soon be over if Danny didn’t stop eating chocolate and feeling so stupid and sad. What more could I say? I wanted this Night of the Wolf, not any other—this night, when I was seventeen and the air rose like smoke from the gutter and the ice shone like glass upon the street.

“Hell, you’re one of the Orphans, aren’t you? You think they would have you if you were dumb?”

They would indeed; Danny was always good for a ride or an alibi, I knew that. But Danny the Sweet didn’t have to know. What the hell.

“Yeah.” Danny nodded. “Yeah.” He smiled.

Good. I had talked him into temporary smartness.

“Let me go with you,” I said.

“This one time,” warned Danny the Sweet. “O.K. But only this one night.”

That was all I needed; for I knew that this was my night; full of smoke and winter and wolves. This was my night.

“Anything you say, Danny,” I told him.

The hour was growing late; and Monty sat somewhere in the darkness of the candy store, drinking one gin after the other, and the corner kids stood at a safe distance from us, warily reading the emblem upon Danny’s back. “Anything you say,” I repeated.

Danny nodded and began to walk down the Avenue; I followed. “You’re not taking your car, Sweet?” I asked.

“Are you crazy?” he said. “Are you crazy? This is a secret meeting of the Orphans. The Pack could easily follow my car, see? We walk.”

I followed him through the mazes of alleyways that led to wherever the Orphans were.

“Remember not to look at anyone,” said Danny. “And whatever happens, don’t say a word to the Dolphin.”

So the Dolphin would be there tonight. I hadn’t thought of that. How could this idiot Danny the Sweet take me where the Dolphin would be?

“What if the Dolphin talks to me?” I asked.

Danny the Sweet stopped in his tracks. Snow fell, and as Danny fumbled for a cigarette, our boots were covered in white. We stood now somewhere close to the City Line, in the territory known as the Orphans’, north of an invisible line that stretched across the Avenue.

“Honey,” said Danny the Sweet, “don’t worry about that. The Dolphin ain’t going to talk to you, see? No one’s going to talk to you. If you and me both is lucky, no one will even notice your presence. The Orphans is particular about who they address themselves to. So just shut up.”

“Drop dead,” I said to the Sweet.

“Now, now,” said Danny. “You are just a girl, and not even the Property of the Orphans gets to speak at meetings, see?”

“Hah,” I said. What had the Property to do with me? Those girls in mascara and leather and silence who belonged to the Orphans.

“Look,” said Danny. “After McKay, the Dolphin is the main man. And the Dolphin talks to few.”

O.K., I thought. Why should I be offended by the words of the Sweet? It was not everyone who got to sit in the same room as McKay and the Dolphin on the Night of the Wolf. Especially McKay. Why should I lie? This was the night I had waited for; to finally meet McKay. What did I care about the Pack? What did I know of revenge or of blood on the streets? It was McKay, President of the Orphans since the death of Alf Cantinni four years before, whom I cared about. So I said to Danny as we walked in the snow, “You tight with McKay?”

>

“Sure,” said Danny. “Doesn’t he call me brother?”

“Doesn’t he call everyone that?” I asked.

“Hah,” said Danny the Sweet.

“How well do you know McKay? I mean, he really talks to you?” I said.

“Cease with the questions,” Danny said.

The Sweet didn’t have to respond to my questions; and he probably didn’t know any answers. I knew that secrets surrounded the Orphans. All that I knew of them I had heard from Danny, or from the liquor-coated stories Monty told each morning as we had coffee at the counter of his store and he repeated rumors that had blown in through his door off the wind of the Avenue.

Like the corner kids, I could only read the Orphans’ colors on the backs of their leather or denim jackets. Jackets I had seen loitering on the corners, loafing outside the Tin Angel Bar, hovering at the doorway of Monty’s.

McKay—I knew something of him. I had memorized the lettering on the back of his leather jacket.

PRESIDENT OF THE ORPHANS

I could conjure the name, the sound of his boot heels on cement; I could recite the number of the license plate of his ’59 Chevy in my sleep. McKay—President of the Orphans at seventeen, sworn into office on the night of Alf Cantinni’s death. An hour after Cantinni had totaled his Corvette, the Avenue knew that McKay was now President; for four years the Avenue had known the name of the leader of the Orphans.

First in line was now the Dolphin; and secrets surrounded him like ice-coated cement in the streets of January. About him, I’d rather not know. Some said, and perhaps it was Monty who began the story, that it was the Dolphin himself who had begun the Night of the Wolf some years ago. Some said that was how the paintings on his skin had begun. But some said a lot of things.

All I knew was filtered through Danny the Sweet and Monty; so I took it all through a haze of cough syrup and gin. I wanted to see for myself, now—enough of leaning over the Sweet’s aging Pontiac to catch the details of the Orphans’ activities while I was splattered with oil. Enough of deciphering the brogue and the lies of Monty’s stories as he mixed up milk shakes for the corner kids, and rumors for me. I wanted to find out for myself.

Now we reached the edge of City Line; the last border of the Orphans’ official territory. The Sweet hesitated. “From now on,” he said, “you blind.”

“Sure,” I said. But I was tracing road maps, alley maps, the drawings of frantic directions on the lining of my jacket pocket. “Sure,” I said.

We walked past St. Anne’s. Lights flashed colors and the sound of a Temptations record poured onto the street from the chapel.

“Knights of Columbus,” said the Sweet. “To keep us off the street on the Night of the Wolf.”

We were now conspirators, so Danny the Sweet winked at me. Groups loitered on the steps of the church; bottles of Thunderbird wine cloaked with brown paper bags were passed from one dancer to another. As Danny and I walked on, the crowd let us pass by with mumbled words about the Orphans and stares at the colors of Danny’s jacket. Danny the Sweet turned up his collar against the wind, and he winked at me once more.

Those dancers should have known what kind of Orphan was Danny the Sweet. Maybe that was why I felt no fear as we turned into an alleyway off the Avenue a block away from St. Anne’s. Did I imagine that the Orphans were all like Danny? Smarter, maybe, but with kind, chocolate-covered hearts.

Danny stopped.

“The clubhouse?” I whispered.

He nodded. “Forget you ever saw it,” he said.

It was the basement of Munda’s City Line Liquor Store. The home of the Orphans. But as Danny climbed down the cement steps to the basement landing I lingered behind.

“Hey, hey,” whispered Danny the Sweet.

I followed; and then I rested my hand on the cold metal of the banister and hesitated.

“Hey.” The Sweet’s voice rasped.

So I followed. What could I do? Sometimes it’s too late; sometimes you walk down the steps, frozen with ice, your hand resting upon the metal banister. You walk into darkness where no neon reaches. “Danny?” I whispered.

“O.K., O.K.,” answered the Sweet.

I found Danny’s arm and held on to him, and we waited outside the door of the Orphans’ clubhouse, both of us knowing that the door would open without us knocking our fists upon it. Sometimes you know when doors will open; you have only to walk up to them and wait.

The light spilled out onto the cement where we stood. I was holding tightly on to the arm of the Sweet, who was sipping ginger ale and blinking his eyes.

“What are you, Sweet, waiting for July?” someone said.

Danny the Sweet giggled. Always an inappropriate response, a giggle, when caught in an act of fear. Even I knew that much.

“Admiring the ambiance of your surroundings,” I said. What the hell, as Monty often said, a word was often the best defense.

“Oh, yeah?” The voice at the door sounded nasty.

“Who is that?” I whispered to Danny the Sweet. “Only Tosh,” whispered Danny, and I could see now the shaven head of one of McKay’s most feared soldiers. “He’s not so tough.” The Sweet gulped more ginger ale.

“Evening, Sweet,” said a voice behind us on the stair.

Danny turned. I stared at the cement, as advised.

“Evening, McKay,” I heard the Sweet say.

So. McKay. I forgot cement, and Tosh at the doorway, and melted ice seeping into my boot. I forgot fear of alleys and the lyrics to all the songs I ever knew. And I remembered only how many girls in Brooklyn and Queens had carved McKay’s name into their thighs with slick razor blades. His name in hearts on subway trains and in toilets. President Of. McKay. I could not help but turn.

“Cold Night of the Wolf, brother,” McKay said to Danny the Sweet.

“Sure is,” mumbled the Sweet.

I forgot myself, forgot that I too stood in that cold stairwell with Danny and McKay. McKay—well, he didn’t look evil, but he sure looked bad. His long dark hair fell upon the collar of his leather jacket, his face, unlike so many of the Orphans’, was unscarred; I could now understand why so many legs had been marked with the initials of his name.

And then I remembered I was there in that alleyway, for McKay’s eye had seen me, and he nodded. I owed it to the Sweet to keep quiet, so I only nodded back. McKay walked past us in that beam of light which fell from the clubhouse door. The letters, red and gold, glowed on his back, the pink motorcycle goggles he wore gleamed electric. McKay opened the door of the clubhouse wider, greeted Tosh, and then, his back to us, the letters “President Of” spotlighted, McKay spoke.

“If you are hip to the ambiance,” he said—McKay actually formed those words in his throat, “wait till you see the decor.”

So McKay had heard me, had addressed himself to me. Perhaps I should have been surprised, but I was seventeen and the moon was circled with frost and I could not have imagined McKay not speaking to me. I could not have imagined the Night of the Wolf did not belong to me. Danny the Sweet, however, was taken aback; his jaw was slack and his eyes blinked.

“You are causing a draft,” said Tosh, who had come out onto the landing to grab the Sweet by the jacket collar and lead him into the basement. I followed—Tosh or the Sweet, who knows? One Orphan jacket looks like any other after you’ve seen “President Of.”

Sometimes you know whether or not it’s your night. Sometimes you don’t. I wasn’t sure. And as I stepped into the clubhouse that first time, I did take McKay’s advice. I checked out the decor, mainly because I didn’t want to look anyone in the eye. Orange crates and mattresses, wooden chairs and posters with ripped corners advertising car races and demolition derbies, some with McKay’s name in small print along with a description of his Chevy. Pillows and cushions and smoke. Your basic basement clubhouse, I assume.

Except for the fact that the basement was populated with Orphans and the Property of the Orphans. I had never seen them all together in one ro

om. One small room with a ceiling of water pipes steaming, one room full of leather and dark eyes and smoke. And now, as I sat on a cushion near Danny the Sweet—I didn’t even want to look the Sweet in the eye—I thought of only one thing. Leaving.

And then McKay spoke. He sat on a crate near the cement wall, boots propped up on a footstool, his long hair constantly pushed back as he ran his hand along his forehead. He smiled into the darkness of the room, and I thought no more of leaving.

“Brothers,” he said. The noise in the basement began to subside; the air itself seemed to clear of smoke.

Around the room I could see the figures of the silent Orphans. Tosh, with his shaven head, just released from the Joint after eighteen months to five (the charge—arson; the target—his brother-in-law’s Mustang), lounged on the floor. Not far from Tosh was T.J., another of the Orphans’ soldiers. Small and pale with wispy blond hair, T.J. crouched upon a mattress. The rumor was that T.J. kept losing parts of himself. First a hand, as he leaped toward a freight train and an attempt to travel free to Elizabeth, New Jersey. And then some toes as a Harley, driven by one of the Pack, gave him a dancing lesson. And now I saw he wore a black patch over his left eye. With anyone else I would say the patch was for effect, but T.J.’s eyeball was probably rolling down some alleyway.

Most of the other Orphans—Jose, Little Doug, Menza, and the rest—I had seen racing their cars on the Avenue or loitering in one doorway or another. But now in the dark, in the cold, in the night, with the jackets of their colors, with their sunglasses, their cigarettes, and their closeness to me, I knew why their names were only whispered on the wind of the Avenue. And now they were the fifteen or so shadows that lined the walls of this one room, the room I was in. And then up against the farthest wall: the Property of the Orphans. They sat in a line, in high, black boots and darkness, all of them silent with their eyes on McKay. I had often seen the Property in Woolworth’s, where scarves flowed into their purses and eyeliner jumped from the counters into their jacket pockets. I had often seen them on one street corner or another, silently waiting for the Orphans, with the insignia upon their backs:

The Story Sisters

The Story Sisters Local Girls

Local Girls Blue Diary

Blue Diary The River King

The River King Here on Earth

Here on Earth Illumination Night: A Novel

Illumination Night: A Novel The Marriage of Opposites

The Marriage of Opposites Nightbird

Nightbird Incantation

Incantation Skylight Confessions

Skylight Confessions The Ice Queen

The Ice Queen Second Nature

Second Nature Fortune's Daughter: A Novel

Fortune's Daughter: A Novel Seventh Heaven

Seventh Heaven The Rules of Magic

The Rules of Magic The Red Garden

The Red Garden The Third Angel

The Third Angel White Horses

White Horses Property of / the Drowning Season / Fortune's Daughter / at Risk

Property of / the Drowning Season / Fortune's Daughter / at Risk Angel Landing

Angel Landing Magic Lessons

Magic Lessons Turtle Moon

Turtle Moon Aquamarine

Aquamarine The World That We Knew

The World That We Knew Faithful

Faithful The Dovekeepers

The Dovekeepers The Foretelling

The Foretelling Green Angel

Green Angel At Risk

At Risk Green Heart

Green Heart Fortune's Daughter

Fortune's Daughter Faerie Knitting

Faerie Knitting Incantation (v5)

Incantation (v5) Green Witch

Green Witch Practical Magic

Practical Magic The Museum of Extraordinary Things

The Museum of Extraordinary Things The Probable Future

The Probable Future Illumination Night

Illumination Night The Dovekeepers: A Novel

The Dovekeepers: A Novel Property Of, the Drowning Season, Fortune's Daughter, and At Risk

Property Of, the Drowning Season, Fortune's Daughter, and At Risk