- Home

Page 2

Page 2

The Story Sisters

The Story Sisters Local Girls

Local Girls Blue Diary

Blue Diary The River King

The River King Here on Earth

Here on Earth Illumination Night: A Novel

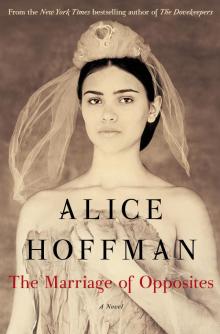

Illumination Night: A Novel The Marriage of Opposites

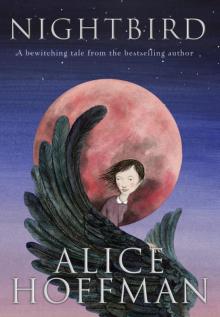

The Marriage of Opposites Nightbird

Nightbird Incantation

Incantation Skylight Confessions

Skylight Confessions The Ice Queen

The Ice Queen Second Nature

Second Nature Fortune's Daughter: A Novel

Fortune's Daughter: A Novel Seventh Heaven

Seventh Heaven The Rules of Magic

The Rules of Magic The Red Garden

The Red Garden The Third Angel

The Third Angel White Horses

White Horses Property of / the Drowning Season / Fortune's Daughter / at Risk

Property of / the Drowning Season / Fortune's Daughter / at Risk Angel Landing

Angel Landing Magic Lessons

Magic Lessons Turtle Moon

Turtle Moon Aquamarine

Aquamarine The World That We Knew

The World That We Knew Faithful

Faithful The Dovekeepers

The Dovekeepers The Foretelling

The Foretelling Green Angel

Green Angel At Risk

At Risk Green Heart

Green Heart Fortune's Daughter

Fortune's Daughter Faerie Knitting

Faerie Knitting Incantation (v5)

Incantation (v5) Green Witch

Green Witch Practical Magic

Practical Magic The Museum of Extraordinary Things

The Museum of Extraordinary Things The Probable Future

The Probable Future Illumination Night

Illumination Night The Dovekeepers: A Novel

The Dovekeepers: A Novel Property Of, the Drowning Season, Fortune's Daughter, and At Risk

Property Of, the Drowning Season, Fortune's Daughter, and At Risk